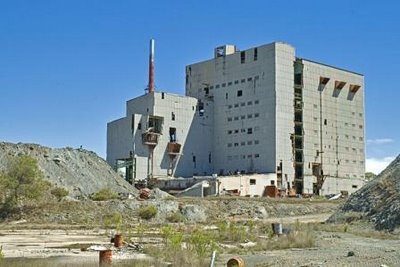

Photo: Gordon Smith, Woodsreef Asbestos Mine

In an earlier post, History of New England, Australia - Pause for Reflection, I commented that I really needed to say something about the early history of mining in New England before talking further about the history of agriculture.

This rather dramatic photo by Gordon Smith shows the abandoned mine workings at the Woodsreef asbestos mine near Barraba.

About 18 km from Barraba are Woodsreef and the Ironbark Creek picnicking and fossicking area.

Gold was discovered at Woodsreef in the late 1850s and a thriving village soon developed with a post office, stores and school, but it virtually disappeared when most miners left in the late 1860s.

White asbestos was first mined at Woodsreef from 1919-1923. In 1972 a large open-cut asbestos mine was opened, furnishing much local employment before closing in the 1980s leaving unremediated mine workings that have become a tourist stop in their own right.

While now dominated by coal mining, New England has been one of the world's major mineral provinces. Given this, I find it odd that we do so little to present the history, romance and attractions associated with mining in a way that will make the experience more accessible to both visitors and locals.

Mining is often presented as beginning with coal extraction by the early convicts at Newcastle. In fact mining predates European settlement. In the words of Geoffrey Blainey's Triumph of the Nomads:

"At Moore Creek. near Tamworth in New South Wales, an outcrop of greywacke running along the crest of a saddle-back ridge was mined prolifically; the axe-stone was quarried by aboriginals for a length of three hundred feet and to a maximum width of twelve feet. On countless still days the noise of the chipping, the patient chipping, must have carried across the slopes.

As the written records were thin in tracing the trade in stone axes from the Tamworth district; other ways of reconstructing the extent of the trade were needed. Petrological analysis was one promising technique. It has been applied as long ago as 1923 to reveal that the so-called bluestone used in building Stonehenge in southern England had been carried all the way from Pembrokshire in Wales.

With this technique in mind an enterprising archaeologist, lsabel McBryde, examined a total of 517 edge-ground axes which had been found scattered over a large part of New South Wales. She mapped the places where each stone axe had originally been collected old aboriginal camping grounds, trade routes, or simply places where an aboriginal had lost or broken his axe or had bartered it away to a European pioneer. In the laboratory a thin sliver of stone was sawn from each available axe. Each specimen of stone was then ground down to a transparent thinness and examined under the microscope of the geologist, R.A. Binns. Once the minute characteristics of the stone had been identified, the search for its place of origin could be concentrated on those regions or even specific hills or valleys which were known to contain that type of stone. In those areas which had been mapped with intensity the exact quarry which produced some axes could even be located. Binns and McBryde were able to name one quarry which had originally produced the stone for sixty-five of the axes that were found in scattered parts of New South Wales.

This kind of archaeological jigsaw the exact matching of axe and quarry can be solved only when every likely source of stone has been discovered and described. In a sparsely-peopled territory the mapping is slow and the geological knowledge is not easily gathered. Nonetheless Binns and McBryde were able to gauge the extent of territory or market which was supplied with stone axes quarried from the long ridge of Moore Creek or from similar rock formations to the north of Tamworth. They found that axes had gone overland through a chain of tribal territories to Cobar, Bourke, Wilcannia, and other points on the plains as remote as 500 miles from the home quarries.The longest of these routes, transposed on to a map of western Europe, was almost equal to a walk overland from the English Channel to the Mediterranean."

I spoke at personal level of the work of Isabel McBryde in my post on the New England writer Patrice Newell.

No comments:

Post a Comment