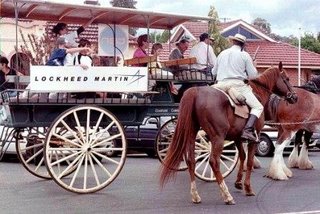

Photo:

Photo: Northern

mail train.

Returning to the history of New England, I began a post discussing the rise of agriculture then realised that there was a missing building block that needed to be filled in first, the railways.

In earlier posts I discussed the impact of transport costs on early European settlement (see

here for a stocktake summary of earlier historical posts), pointing also to the way in which geography, transport and fights over transport helped shape New England's history.

The first railways in New England were the coal tramways in the lower Hunter. This was followed by the construction of Great Northern Railway - by far the largest construction work in New England in the 19th century - linking Newcastle with Tenterfield and the Queensland border. Spurs were built from this line to open new agricultural areas. Then the first decades of the twentieth saw the progressive completion of the North Coast line.

Railways, their construction and impact, were a constant theme in New England politics.

The railways encouraged the spread of agriculture, especially wheat, in inland New England, leading to the growth of centres such as Tamworth and Inverell.

The progressive construction of the Great Northern Railway had other profound impacts on towns along the route. Small local industries - soap works, breweries are examples - vanished in the face of increased competition. Traffic was diverted from the river ports to the new railway, briefly creating what Lazlo called an economic commonwealth centred on Newcastle, before the opening of the Hawkesbury River bridge diverted Newcastle traffic to Sydney.

In earlier posts (

here and

here) I looked at the history of inland river transport as a case study in inter-colonial rivalry, at the way in which transport policy was used to benefit commercial interests in the respective capital cities, to centralise traffic.

The New England railways reflected this pattern. Freight rates were set so as to benefit the whole system, and that effectively meant Sydney. Initially the rates were designed to attract traffic from rival transport modes. Then when the line from Sydney to Newcastle finally opened, freight rates on that line were set so as to divert traffic from Newcastle to Sydney. This effectively meant that some northern freight was initially carried at zero rates on this last stretch.

Economic concepts such as network economics or the multiplier had not then been developed, so people lacked the analytical tools that we have today to look at impacts. This is not insignificant. Had the multiplier (the way in which one dollar of spend creates further spend) been invented, the negative static financial analysis used to discredit the proposed Northern New State during the 1924 Cohen Royal Commission could itself have been discredited.

But while people lacked the tools, they were not blind to the practical effects of the railways and railway policies. The need for east-west linkages was a constant theme. From the Hunter Valley in the south to the far Northern Tablelands, from the 1880's to the 1950's, lines were proposed, some were approved by the NSW Parliament, construction even started in at least one case, none were finished.

The first part of what would become the North Coast rail line - in this case linking the Tweed with the Clarence and the rival river ports with their most immediate hinterland - was approved by the Parkes Government as a compromise to a rival east-west proposal. The problem in all cases lay in trenchant railway opposition on one side, rival and fragmented local interests on the other.

The North Coast line, built in fits and starts from Maitland to the Queensland border, finally allowed through traffic from Sydney to Brisbane from 1930, although a train ferry was still required at Grafton until the bridge over the Clarence was completed in 1932.

Blocked from east-west traffic, now facing direct north-south competition from rail, the North Coast ports entered their final decline. Of all New England's ports, only Newcastle would survive and prosper because of its industrial base and its role as a coal export port.

The bifurcation of New England into two north-south zones - an inland and coastal strip zones -was now complete, although it would take a number of years before the effects were fully felt, including the rise of the coast and parallel decline of the inland.

Initially Brisbane-Sydney rail traffic was carried on both lines. As a child I remember the haunting early morning wail of the Brisbane Mail as it passed through Armidale, of getting up early so that Dad could catch the Brisbane train. But traffic steadily passed to the upgraded coastal route, finally culminating in the closure of the Great Northern Railroad north of Armidale.

Initially, too, the New England Highway remained the main north-south traffic route. The Pacific Highway was narrow and winding and even in the 1960's punts were used to cross certain rivers, leading to longish waits. Again this period is imprinted on my memory in part because of the sounds, in this case the trucks changing gear in the early morning as they climbed the hill two blocks west of our home.

Again, even in the 1960's population structures in inland and coastal New England were similar outside Newcastle as New England's biggest city. While inland New England was losing young people (by 1960 as many people born on the Northern Tablelands lived elsewhere as lived on the Tablelands itself), Armidale and Tamworth were comparable in size to Lismore or Grafton as the biggest coastal cities, Inverell was bigger than Coffs Harbour.

Even though there were no east-west railways and in fact few tarred roads (the first tarred road to the coast dates from the early sixties), the east-west links established by history and maintained through the campaigns of the New England New State Movement were still apparently strong.

To my mind, the turning point came in 1967 with the narrow defeat of the New State plebiscite. Much of New England voted yes, with majorities over eighty per cent in some booths. However, the ALP, fearful of being locked into a minority position in any New England State, mounted a powerful campaign against.

Polling before the vote showed that if Newcastle people were asked the question, if there is to be a New England New State should Newcastle be part, there was a clear yes majority. If the question was rephrased to say, Labor is opposed to the New England New State, do you support it, the yes vote dropped to 30 per cent.

The anti-new state campaign by Labor gathered most of the Labor faithful in Newcastle and the coal mining areas into the no camp. There was also a strong no campaign among dairy farmers in the lower Hunter fearful of losing access to the Sydney milk market. Together, this powerful no vote was just sufficient to defeat the plebiscite.

The issue of inclusion of Newcastle in New England had been a vexed one among some New Englanders. However, the reality was that the Hunter had always been part of New England in geographic terms. Further, Maitland as the junction point for the Great Northern and coastal rail lines needed to be included, and you couldn't really put a state boundary through the middle of the Hunter Valley. All these factors had combined to lead the 1930's Nicholas Royal Commission, the second Royal Commission forced by the New Englanders, to recommend boundaries including Newcastle.

At the time of the defeat the New England New State Movement had been campaigning in a sustained way since the end of the Second World War. Well over a 100,000 pounds had been raised and spent on campaigning, especially since the launch of Operation Seventh State in 1961. Exhausted and dispirited, the Movement collapsed. With it went the political cohesion that had been holding New England together.

Since then, New England has fragmented into a series of competing localities and sub-regions. It has lost much of the sense of its own identity and has declined in influence across every dimension.

In a small way, this blog is an attempt to bring it back, to capture and present the New England experience. I was and remain a proud New Englander.