By accident of political geography, most people think of New England in north-south terms. When thinking of New England in colours it is better to think west-east.

New England's colours do change north-south. However, those changes are more gradual because New England's main geographic regions - coast, tablelands, western slopes and plains - run north-south. The traveller sees changes, but these are gradual, muted. Travelling west-east we transect zones, crossing sharply from one to another. Differences stand out more clearly.

out more clearly.

This photo by New England photographer Gordon Smith shows the country south of Bourke. The ground is bare, red to ochre tones. The trees have an olive green hue. The flat plains in this region make for a vast sky that can be intensely blue. The passage of the moon casts a glow across the plains. On moonless nights the panoply of the stars stand out bright against a black sky.

The same things are true further east. But as you move east there are more lights to dull the stars, more hills to break the the sky.

New England's rainfall declines east to west, so you as you move east rainfall and hence ground cover increases.

The following photo was taken only a few hundred kilometres from the first one. You can see the same flat plains, the same olive colouring, but now there is grass.

During good times, these paddock s are under wheat. The photo was taken in drought. During drought, the colour of the grass changes. It becomes greyer, sometimes almost transparent.

s are under wheat. The photo was taken in drought. During drought, the colour of the grass changes. It becomes greyer, sometimes almost transparent.

Eldest went to this property for the twins' twenty first.

The twins boarded at her Sydney school. We went though almost the entire school period without realising that we were part of the same extended family.

The party was a real culture shock for many of the city girls. They had never been to the country, let alone a big country property in the midst of a severe drought.

The New England Tablelands forms the central core of New England. Rivers flow to the west from the Tablelands, separated by ranges. These ranges provide another element in the colours of New England. In the distance, they appear a hazy blue. Close up, they acquire a more olive green tone.

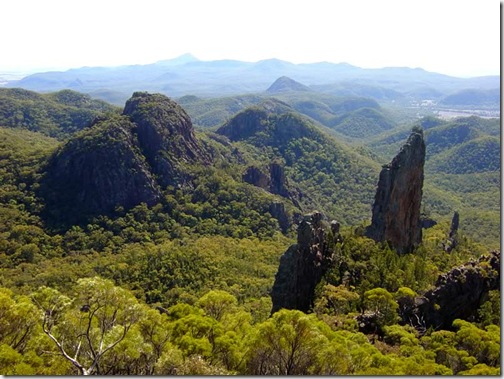

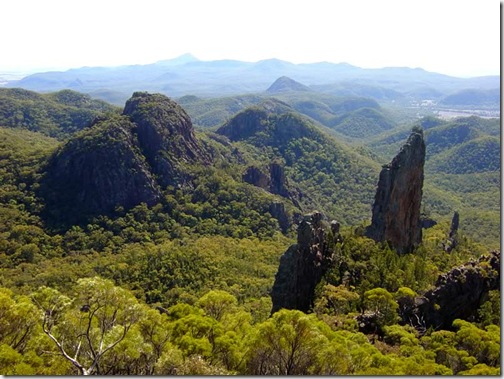

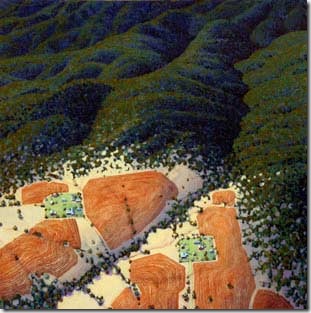

This photo is of the Warrumbungles. You can see the colour gradations.

In the far distance you can see the hazy blue. Close up, there is a golden colour fading into olive green.

Gold is another colour of New England. The gold of wattles: while their colour merges with the olive green of the trees, wattle still stands out. Beyond this, many of the trees have a yellow tinge, as do some of the soils.

The western river valleys that lie between the old remnant western mountains begin small in their New England Tablelands headwaters but then broaden and flatten. At 1.2 million hectares, the Liverpool Plains is vast in its own right.

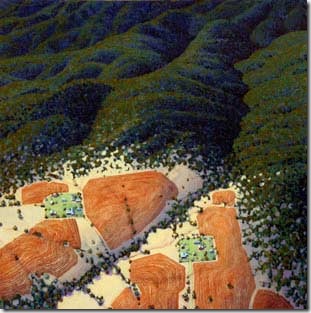

Black soils, red soils, yellow soils support the New England wheat crop. Remnants, a painting by New England painter  Harry Pidgeon, shows the colour patterns.

Harry Pidgeon, shows the colour patterns.

Now on the Liverpool Plains another colour, the black of coal, is in competition with the the varied hues of soil and crop for dominance. The battle between farmer and miner has been a harsh one that continues.

The rivers that flow through these valleys to help form the Darling River can be slow and meandering. At times they cease to flow entirely. Then, at flood, they can carry enormous volumes of water submerging towns and farms alike. Movement becomes impossible. It is no coincidence that the debut album of New England song writer and singer L J Hill was called simply Namoi Mud.

These rivers are now the centre of another clash of colours whose epicentre lies far to the south. The diminishing muddy brown of the once mighty Murray River competes with the white of the irrigated New England cotton crop, the gold and yellow of irrigated wheat and sunflower. To some degree the agricultural expansion of New England is being wound back to feed the water needs of people living thousands of miles away, to satisfy the demands of urban environmentalists, to solve the problems of a much bigger but grossly over-used river. New England has more water, that's the key.

As the rivers approach the tablelands agriculture merges into bush; gold is replaced by live green. Another Harry Pidgeon painting, Edge, captures the transition.

We now enter another world.

The Northern or New England Tablelands stretches from the Barrington Tops and Liverpool Range in the south to just past the Queensland town of Stanthorpe in the north, a strait line distance of over 440 kilometres. This is Australia's largest tablelands area, one whose sheer size makes for its own variety.

We have now entered the world of the New England poet and writer Judith Wright whose family established a chain of pastoral properties extending from the family head properties on the eastern edge of the Tablelands up the plains and slopes into Queensland.

South of my day's circle, part of my blood's country

rises that tableland, high delicate outline

of bony slopes wincing under the winter,

low trees, blue leaved and olive, outcropping granite -

Notice the colour. This is a different world, both softer and harsher than that further west. The photo of Cooney Creek by Gordon Smith captures the way in which mist can gentle the countryside.

Tableland's granite adds a new colour, gray. Granite is gray or sometimes gray white. Granite soil can be very poor; clean, lean, hungry country to use Judith's words.

The early European settlers liked the Tablelands in part because it reminded them of home.

The high value of wool built dynasties that in many ways aped the world of the home countries. They modified the landscape through planting, introducing new colours - the deeper green of elms and oaks; the change of colour that marked the seasons. Ivy covered buildings.

There is an enormous difference between the harsher reds, yellows and golds of the western slopes and plains and the reds and golds of a Tablelands autumn. Red and gold - we can see the difference in the differences between Tamworth and Armidale.

Armidale, still the capital in waiting for the self-governing New England state so many of us have sought over so many years, is in some ways a genteel city.

Armidale, still the capital in waiting for the self-governing New England state so many of us have sought over so many years, is in some ways a genteel city.

This photo, again by Gordon Smith, shows red, gold, green and blue framed around Armidale's Anglican cathedral.

Not everyone likes Armidale. Greg Shortis, one of the Armidale poets, wrote:

Scabrous little dump,why should I give a stuff

About your aldermen and your counterculture

Making great stumbles forward into the future?

Why should I stumble over your great poets?

That bushranger was right

Who observed people travelling in your direction

From behind a rock.

This type of jaundiced view is not uncommon. To many Tamworth people in particular, Armidale is conservative, genteel, behind the times. To many Armidale people, Tamworth is brash, commercial.

The gold of Armidale's autumn colours contrasts with the gold of Tamworth's golden guitar award.

It is no an accident that Tamworth should have become Australia's country music capital. As capital of the Liverpool Plains, Tamworth grew from farming. Australian country music is a music especially of the slopes and plains. Armidale preferred folk or jazz, Tamworth country. Armidale is a world of pastel colours, Tamworth colours are brighter.

To the east and south of the Tablelands the palette changes again. Now we enter the world of the coastal, eastern flowing rivers.

The Hunter Valley in the south is a world of different colours again. While not New England's biggest coastal river valley, the Clarence is 8,800 square kilometres as compared to the Hunter's 8,500 square kilometres, it is New England's longest. From Murrurundi at the head of the Valley to Newcastle at the Hunter River mouth is almost three hours driving time south and east.

Belonging to New England by history, the Valley is increasingly joined to Sydney for planning purposes. The old joke about NSW standing for Newcastle, Sydney and Wollongong has become increasingly true. An arbitrary line has been drawn through the middle of the Valley. The Upper Hunter is allocated to the rest of NSW, the Lower Hunter to Gre ater Sydney.

ater Sydney.

As the road drops down from the Liverpool range into the valley, the mountain bluffs stand out, ringing the valley. We have entered horse country. The green of irrigated fields, the white of fence posts, the horses grazing, stand out.

The photo shows Emirates Park at Murrurundi. This is one of the oldest studs in the valley. Further south, Scone lays claim to be the horse capital of Australia. Nearby Gundy is the headquarters of the Packer Family's polo interests.

Like the Liverpool Plains, black is the new gold in the Hunter. The huge coal seams that stretch up the Valley and onto the Liverpool Plains The huge coal trains that wend their way south to the clogged and overcrowded port at Newcastle are gray by paint and coal dust. The only colour comes from the dusty engines and the sometimes graffiti on the rolling stock.

As in the Liverpool Plains, coal has become an environmental flash point.

The grape and olive growers whose vineyards and plantations dot the Hunter and provi de both the colour and taste that attracts visitors, protest about the potential damage to their crops. In Newcastle green protestors attempt to block expansion, a view not shared by miners further up the Valley.

de both the colour and taste that attracts visitors, protest about the potential damage to their crops. In Newcastle green protestors attempt to block expansion, a view not shared by miners further up the Valley.

At Newcastle we reach the point of interactions between sea blue, sky blue and people.

Coastal sky blue is not the same as that further inland. Clouds and haze mute the colour to some degree. The night sky is not the same either. Lights, cloud and haze mute the colours. People rarely look up at the giant bowl of the night sky.

From Newcastle north along the coastal strip to the border the key colours are blue, green, gold and brown. The blue of sea, sky and the nearby ranges; the varying shades of green of the vegetation; the gold of the beaches; and the generally brown rivers flowing from the mountains to the sea.

A remarkable number of the new settlers that have moved to the coastal strip in recent years live in a narrow strip/ To many, the distant blue of the ranges marks a barrier. The colours of New England have shrunk, the palette reduced to just a few colours

In some ways this is the world of the ABC TV series East of Eden. While loosely set in and filmed around the now very trendy resort centre of Byron Bay, this series was marked by a disconnect with real life. One viewer wrote:

They were too new-age, too involved with themselves. Frankly, I thought they were a bunch of tossers, and it seems, going by the ratings, that a lot of other viewers thought likewise.

While I don't fully share this view, East of Eden does mark a truncation of the view of coastal New England in the external world to a narrow slice.

Again, the best way of seeing the changing colours of New England is to keep moving east. As we move up onto the Tablelands from the west the trees change colour. There is more green and olive green, less light green or brown.

Moving further east, the Tablelands are deeply marked by huge gorges cut deep into the country by the rivers and streams flowing to the coast.

We have entered the world of the escarpment where, as this photo by Gordon Smith shows, ranges pile on ranges moving from blue-green to blue with distance. Then, suddenly, the roads drop sharply as they wind their way down. Now we have the different green of ferns, clear running water, the sound of bellbirds. This some of New England's most beautiful country.

I have often wondered why people spend so little time in the upper reaches of the coastal valleys. Some parts are well known.

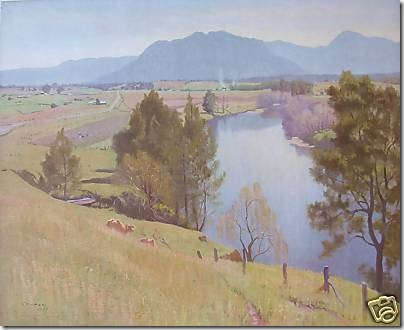

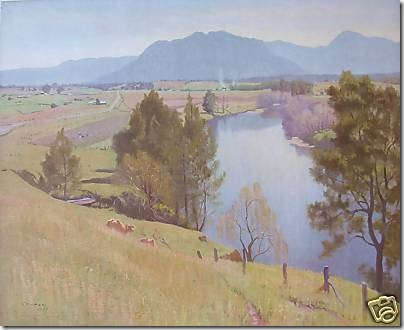

This painting by Elioth Gruner shows the Bellinger River Valley looking back to the distant mounta ins. This valley is well known, with the town of Bellingen now well known counter-cultural centre. Other parts such as the Upper Macleay are less recognised.

ins. This valley is well known, with the town of Bellingen now well known counter-cultural centre. Other parts such as the Upper Macleay are less recognised.

The distance between mountains and sea varies enormously. In places, the ranges crowd the coast.

In others and especially in the Hunter and Northern Rivers - the Clarence, Richmond and Tweed - the hinterland is substantial. Grafton itself, once the dominant river port, is just under an hour's drive away from the river mouth at Yamba.

Perhaps the first thing that an inland person notices about the coast is just how green the grass is. The upper river valleys can be very brown, but green is dominant. This holds true, too, for the sugar cane fields from Grafton north.

The next thing an inland person notices are the rivers themselves. To inland eyes these, and especially the Clarence, are big rivers.

The sheer size of the Clarence makes for great visual variet y in the physical and built landscapes.

y in the physical and built landscapes.

The many little villages such as Ulmarra nestle in the countryside or on the banks; there is a constant sense of discovery.

Still moving west, we finally finish at the ocean.

The red/yellow soils that began our journey have now been replaced by yellow sand.

We have travelled around 8oo kilometres in a straight line, much more if our detours are included. It's time to end the journey and have a beer! Or, in my case, prepare lunch.